Hussein Askary (Vice-Chairman, The Belt and Road Institute in Sweden)

After the “China debt-trap” narrative was thoroughly exposed as a fraud internationally, including through, but not limited to research made by this author, there is a new two-pronged game in town: China must bail out Western bondholders controlling the debt of many nations in distress; at the same time, the International Monetary Fund, the U.S., and the EU are pressuring those nations to abandon infrastructure projects financed by China in return for debt relief. In the case of Zambia, this was made very clear by the IMF. This seems to be goal of the visit of U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen to Zambia, i.e., making Zambia an example or a template for this new push to block the Belt and Road Initiative and China-Africa cooperation which is soundly based on building infrastructure (transport, power, water management, modern telecommunications, healthcare and education) and modern agriculture and industry. This is the way, as China proved it at home, for those nations to escape the double traps of poverty and chronic debt distress. At the same time, the looting of the raw materials of African nations by the former colonial power, especially Britain, continues with greater vigor and malice under the guise of reforms, privatizations, and investment incentives. In the case of Zambia, as we explain here, the situation is probably as bad as it was in the colonial period.

The debt distress experienced by these countries predates Chinas’ involvement through the Belt and Road Initiative in Africa and Asia and was made worse with the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020-2021. It continued as the inflation in global energy and commodity prices continued throughout 2021 and finally dramatically worsened with the outbreak of the Ukraine crisis in February 2022. As we explained in the groundbreaking report on Sri Lanka’s debt crisis in 2022 The nations that rely heavily on imports of fuel, food and fertilizers are the worst hit. Sri Lanka and Zambia are two cases in point. The latter already defaulted in November 2020 on Eurobonds (not Chinese debt service!) and has been negotiating a financial assistance package with the IMF and international creditors. Sri Lanka defaulted in May 2022. These nations had resorted to borrowing heavily from international private bond markets during the COVID-19 pandemic, but even before that.

Here is what happened in Zambia: When the commodity prices plunge took place in 2014, the country entered a major financial crisis, pushing it to resort to borrowing from international private bond markets. In 2014, Zambia issued Eurobonds worth US$1bn, in a deal supported by the IMF and managed by Deutsche Bank and Barclays. In 2015 another US$1.3 billion Eurobond was issued. The interest rate was an incredible 9.3%. Maturity time for these bonds varied between 7 and 11 years. These Eurobond issuances were intended to fill a gap in the budget deficit of US$ 2 billion, and not to invest in any productive processes.

In November 2020, the country defaulted on a US$42.5 million payment on one of the Eurobonds.

Same old IMF recipe

The exact same mistake is being made in the new “debt relief” arrangements of the IMF, which focus on filling fiscal gaps in finances of the government rather than developing the economy. New loans are taken to ease the emergency needs and will be consumed without any impact on improving the productivity of the society. These new loans will mature sooner or later and the vicious cycle will be repeated.

Our study of the demands made by the West on China and of the type of conditions imposed by the IMF on these two nations (Zambia and Sri Lanka) in return for assistance reveal several objectives that could be problematic for China and the Belt and Road Initiative:

- The call on China to provide more assistance in the IMF-driven debt restructuring of these nations imply that China contribute to bailing out the Western private sovereign bond holders, who themselves are pressed by the global financial crisis.

- The IMF is demanding, like in the case of Zambia, to stop borrowing (from China without naming it by name) for important infrastructure project.

- Those two nations are being pressured by the IMF to resort to “public-private partnership” in financing and building infrastructure. This means that many projects will not be achieved as their financial yield would be deemed as too small or non-existent by private investors. Or, otherwise, certain vital strategic facilities like ports and airports will be privatized and owned by foreign interests.

- There is a risk of asset grabbing by the same Western interests and their allies focused on strategic raw materials.

U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s counselor Brent Neiman said in a speech on September 20, 2022 that China’s lack of cooperation with the G-20 and the IMF on debt relief could burden dozens of low- and middle-income countries with years of debt servicing problems, lower growth and underinvestment.

“China’s enormous scale as a lender means its participation is essential”, Neiman said in the speech citing estimates that China has $500 billion to $1 trillion in outstanding official loans, mainly to low and middle-income countries. However, these numbers are difficult to ascertain and it is not clear to what projects and what countries these loans were extended.

On July 14, 2022 US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said on the sidelines of the G-20 Finance Ministers meeting in Indonesia, that “Sri Lanka is clearly unable to repay that debt, and it’s my hope that China will be willing to work with Sri Lanka to restructure the debt.” She also said that China is a “very important” creditor of Sri Lanka, and it would likely be in both countries interest that China participate in restructuring Sri Lanka’s debt. As we explained in our article on Sri Lanka’s debt, not only is China’s share of the country’s foreign debt is a mere 10%, the real culprits that Yellen should focus on are the American and British private bond holders such as Blackrock and Ashmore, who hold 47% of Sri Lanka’s foreign debt. It became obvious that the IMF’s main conditionality to help Sri Lanka was to cut a deal first on repayment of the debt of Western bondholders. The IMF warned in its report after visiting Sri Lanka in September 2022: “Financing assurances to restore debt sustainability from Sri Lanka’s official creditors and making a good faith effort to reach a collaborative agreement with private creditors are crucial before the IMF can provide financial support to Sri Lanka”.

The statements by Yellen and other American officials are being used in Western media to show that China’s unwillingness to help the IMF programs is undermining the efforts to help poor nation with debt restructuring. But China is doing the right thing by avoiding the IMF methods and focuses instead on its own solutions.

Neo-colonial looting of Zambia’s minerals

Zambia is Africa’s second largest exporter of copper and other industrial minerals like Cobalt and gold. But while the mining sector constitutes 70-80% of the country’s exports, it does not contribute more than 4-5% of government revenues, because the mining sector is largely owned by foreign companies, mostly British, or Canadian or Australian (British Commonwealth). The absolute largest of these are: Glencore Plc (Glencore Xstrata Plc), Konkola Copper Mines Plc (Subsidiary of Vedanta Resources), Barrick Gold Corp, First Quantum Minerals Ltd, Axmin Inc., Caledonia Mining Corp, Lubambe Copper Mine Limited, Trek Metals Limited (Zambezi Resources Pty Ltd).

Only one major company is Chinese, China Nonferrous Metals Corporation (CNMC).

Most of the profit from mining does not return to the country. In 2021 Zambia estimated exports were US$8.1 billion. Copper accounted for US$6.1 billion of that (76% of total exports). But only less than US$1 billion was repatriated to Zambia by those companies. These companies do not use local suppliers to the mining operations and all machinery and services are supplied from abroad. The privatization of the mining sector was part of the liberalization process in the 1990s agreed upon with the IMF and Worlds Bank. These policies also made foreign mining companies largely exempt from taxation under the pretext of encouraging more foreign direct investments into the county.

How Glencore and Vedanta are stripping the country bare of copper and returning nothing but misery and pollution is described in detail in the report “The New-Colonialism” (PDF – pages 21-25) by the London-based organization War on Want. The reality is that the British and French empires never left Africa, but simply changed their appearances. This report concludes that as many as 101 companies listed on the London Stock Ecxhange have mineral operations in sub-Saharan Africa, covering 37 countries, and control an identified $1.05 trillion worth of resources in Africa in just five commodities — oil, gold,

diamonds, coal and platinum.

How these former colonial interests marched back into the country is described well, probably unintentionally, in a report made by a team of the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) The sinister methods used to deprive Zambia of its natural resources under the guise of sophisticated liberal economic methods are documented. Here are some of the most interesting conclusions of that report:

- The privatization process was complete in the early 2000s as global demand for base metals, including copper, soared between 2003 and 2011 to above US$8,000 per ton in 2011. Investments by foreign companies picked up, too. Foreign direct investment (FDI) in the mining sector increased to more than 60 percent (US$4.5 billion) of total FDI.

- Despite the price and output booms, weak revenue generation continued even in the post-privatization period. This was a direct consequence of the contractual agreements and associated generous incentives granted to the private foreign mining companies.

- During the privatization process, the sale of Zambia Consolidated Copper Mines Limited (ZCCM) assets was negotiated bilaterally between the government and the mining companies in contracts referred to as “Development Agreements”. The general terms of sale embodied highly generous tax and other concessions. Several issues stand out: there was no VAT charge for mine products; capital expenditure had a deductible allowance of 100 percent; and “stability periods” of 15 to 20 years during which no changes could be made to the agreements.

- Mining companies have been enjoying excise duty rebates on electricity supplied by the state utility firm. A major concern was the low average rate of mineral royalty, which in most cases was set at 0.6% (!!!) and thus way outside the global average range of 2 percent to 6 percent and below the IMF’s own estimates of between 5 percent and 10 percent for developing countries.

- The first batch of privatized companies paid royalty rate of between 2 percent to 3 percent. But this rate was revised downwards following negotiation of a highly generous 0.6 percent by Anglo America Corporation, which was subsequently applied uniformly across all mining firms.

- The Foreign Investment Advisory Service of the World Bank argued that, due to the incentives granted to the mining sector, the marginal effective tax rate was in the neighborhood of 0 percent! The subsidy granted to the purchase of mining machinery, at 18.3 percent, represented the largest in any sector for any asset.

- Price increases generated a permanent income stream in excess of 5 percent of pre-boom GDP, translating into a potential saving of US$1.4 billion (39 percent of 2002 GDP) in net present-value terms. However, the private mining companies, through profit repatriation, appropriated the bulk of this windfall and made dividend pay-outs to foreign shareholders.

Thus, Zambia’s mining tree has been growing, but its fruits have been falling on British soil.

Zambia’s debt composition

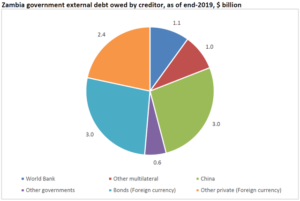

Zambia External Debt reached 17 USD bn in late 2021. Eurobond holders held $6 billion of Zambian debt plus $336 million of interest arrears at the end of 2021. British Abrdn (Aberdeen) is one of the largest bond holders, and it leads a committee of bondholders estimated to hold around 45% of Zambia’s international market debt. Aberdeen and its partners were opposed to any “haircut” to the bondholders in any settlement. American giant investment fund BlackRock holds around $215 million worth of these bonds. BlackRock has reportedly made big profits from these holdings through the years.

By comparison, Zambia’s nominal GDP was reported at 22 USD bn in Dec 2021.

Chinese loans to Zambia account for 30% (or US$ 6 billion) of the total external debt. However, these are long-term loans with long grace periods dedicated mostly to infrastructure projects such as dams and hydropower projects, roads, highways, telecom and digital infrastructure, hospitals, and clean drinking water management systems.

Consequences of Zambia’s deal with the IMF

The most important results of the agreement between the IMF and Zambia’s government to get a zero-interest loan of $1.3 billion with a grace period of five-and-a-half years, and a final maturity of 10 years, was indicated in the reports of the IMF staff. To receive the financial support Zambia had to accept specific conditionalities to reduce government spending, but most emphatically to stop borrowing for infrastructure projects.

The IMF staff report in September 2022 stated clearly: “Zambia is dealing with large fiscal and external imbalances resulting from years of economic mismanagement, especially an overly ambitious public investment drive that did not yield any significant boost to growth or revenues.”, it asserts also that “rapid debt accumulation on the backdrop of deteriorating economic fundamentals has led to unsustainable debt levels and subsequent accumulation of arrears. Debt contracted has mainly been for infrastructure projects in sectors such as roads, education, health and defense.” This is outright sophistry, since the most poisonous part of the debt was accumulated through borrowing in the global bond markets from mainly British and American sources. China’s credits were long term and focused on improving the physical economy and productivity of Zambia.

This has been the demand of the IMF since the previous government started its negotiations. This led the government to cancel a large number of projects mostly agreed with China, but whose loan disbursements were not yet made, according to Finance Minister, Felix Nkulukusa, some of the Chinese Projects cancelled are:

– Major highway – the US$1.2 billion Lusaka-Ndola dual carriageway funded by China Jiangxi Corporation – which was to link the capital to the country’s Copperbelt Province. Lusaka has engaged China Jiangxi to cancel US$157 million in undisbursed loans.

– Digital projects, such as Smart Zambia phase II (US$333.2 million) which was being implemented by Huawei Technologies and funded by China Exim Bank. Digital terrestrial television broadcasting systems in Zambia phases II and III.

– Zambia asked China Exim Bank to cancel US$159 million to fund the building of Chalala army barracks in Lusaka.

– FJT University Under the Ministry of Education.

– Rehabilitation of Urban Roads Phase 3 under the Ministry of Infrastructure and Urban Development.

Conclusion

Given the conditionalities imposed by the IMF and Western partners on Zambia and other countries to cancel vital infrastructure projects, mostly with China under the BRI, it is not reasonable for China to participate in these programs.

When 77 percent of Zambia’s population do not have access to clean drinking water, 60 percent do not have access to electricity, and 46 percent do not have access to the internet, and the roads are in the worst shape, it is unfathomable how cancelling all these infrastructure projects will lead to any improvement in the country’s economy. There is no evidence supporting the IMF Staff assertion that these infrastructure projects “do not yield any significant boost to growth or revenues”. It is a basic fact of economics that improvements in infrastructure lead to direct and indirect increase in the productivity of the economy by creating efficient transport networks, lowering the cost of production through abundant electricity and transport facilities, and increasing access to markets.

The other risk resulting from this policy is that the government will be allowed to continue non-productive public spending such as in payment of public employees and disbursements to mitigate the globally induced inflation. This will increase the non-productive financial burden. At the same time the IMF conditionality of lifting government subsidies on fuel will lead to increase in the cost of production of most commodities potentially leading to public unrest and political instability.

China will be pushed back as a partner and the Western-controlled multilateral partners, like the World Bank will assume the major role through the assistance measures that are directed as social programs to deal with effects of poverty rather than dealing with the causes. This will keep the country, where 60% of the population is under the poverty line, in a permanent state of poverty and reliance on aid programs from the West.

If this push in Zambia succeeds in achieving the goals set by the U.S., the British and their partners, it will be used as a template elsewhere, where this becomes the precedent and standard.

Recommendations

As noted in the beginning of this report, the attempt to pressure China to make concessions to the IMF and other financial institutions is intended to help bailout the private interests in the U.S., and Britain who are themselves under huge risks due to the current Trans-Atlantic financial and banking crisis. The other goal is to block BRI projects, especially in the least-developed countries with large mineral reserves.

China is recommended to make public its position of “no bailout” of private interests whose loans to those countries were not made to benefit those peoples but to make profit in times of crisis. China must make clear that its loans to those countries, especially to build vital infrastructure are “qualitatively” different than the Wester loans, because China’s projects lead to increasing the productivity of those countries and their ability to refinance their debt. Western loans in times of crisis are intended to pay old debt (especially to private interests as argued here by the IMF itself). This kind of credit policy puts developing countries in a real debt-trap and vicious spiral as they are not given the opportunity or permission to invest in productive projects.

China should, otherwise, continue its well-known and documented debt-forgiveness and rescheduling in a case-by-case manner. China’s loans for vital infrastructure projects must continue because China has become the creditor of final resort for such important investments to pull those nations out of poverty. In the worst case, China may shift to “investments” in infrastructure rather than financing and constructing through loans, and secure the mineral resources it needs for its industrial development through win-win cooperation with mineral-rich countries.

African nations have to take control of their natural resources in a fair and organized manner. The neo-colonial methods, as described above, have to be exposed and ended. African nations need to abandon the primitive economic process of exporting raw materials. These raw materials, if processed and manufactured into products inside those countries will add value in many orders of magnitude to the raw materials extracted. The recent case of Zimbabwe banning the export of raw lithium and entering a joint venture with a Chinese company to build a lithium-ion battery plant in the country is a revolutionary move. It has the potential of reconstructing the relationship of the whole African continent with the rest of the world. The age of exploitation of nations through colonialism and neo-colonialism has to end and be replaced by the win-win concept manifest in the Belt and Road Initiative.

Related Items:

High-Level BRIX seminar in Stockholm “The New Africa Emerging” along the Belt and Road.

Check The Facts of Sri Lanka’s Debt Crisis: No Chinese Debt-Trap!